The developed world is much agitated by very low interest rates. Rates are so low that it is hard to imagine them declining further, a situation that emasculates monetary policy.

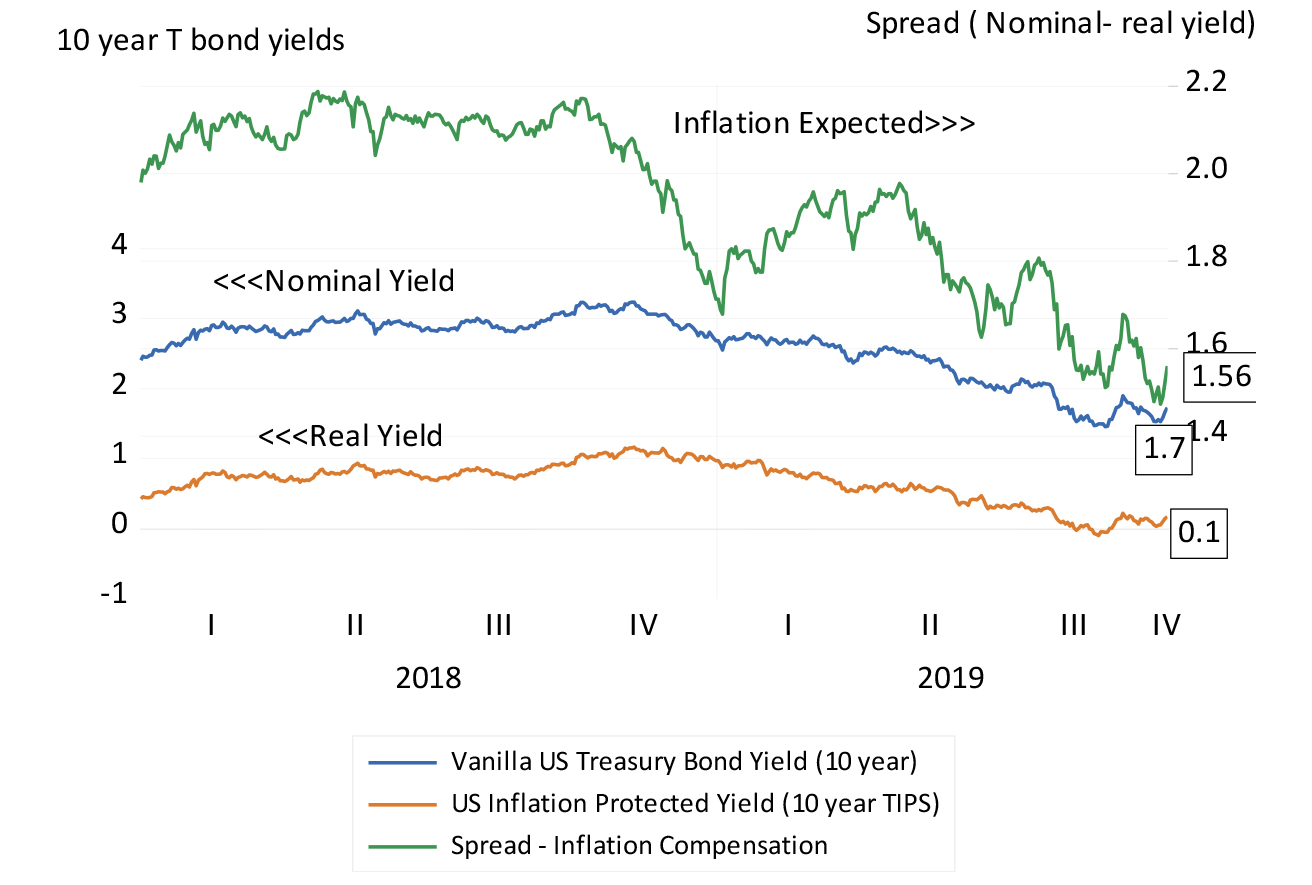

Interest rates reflect a relative abundance of global savings. That’s why inflation (prices rise when demand exceeds available supply) is confidently expected to remain at these very low rates. Interest rates accordingly offer compensation for expected inflation. The US bond market only offers an extra 1.6% annually for bearing inflation risks over the next 10 years (see figure below).

The US Treasury bond market (10 year yields)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

Deflation or generally falling prices, have rather become a threat to economic stability. When prices are expected to fall and interest rates offer no reward to lenders, cash (literally hoarding notes and coins) may be a desirable option. If prices are to be lower in six months than they are today, it may make sense for firms and households to postpone spending, including on hiring labour. Hence even less spent and more saved, compounding the slow growth issue.

An economy-wide unwillingness to demand more stuff is not a normal state of economic affairs. If demand is lacking, resources – land, labour, and capital – become idle. In these unwelcome circumstances, a government and its central bank can always stimulate more spending, including its own, without any real cost to taxpayers or economic trade-offs. More demand means no less supplied – therefore no output or income will be lost and more will be forthcoming, should demand catch up with potential supply.

Most simply, unlimited spending can be encouraged by handing out money or jettisoning cash from the proverbial helicopter. Being able to borrow for 30 years at very low interest rates is as inexpensive a funding method for a government as printing money.

One can expect unorthodox experiments in stimulating demand – should the developed economies continue to grow very slowly – and interest rates and inflation to remain at very low levels until growth and inflation pick up. Cutting taxes and funding a temporarily enlarged fiscal deficit with money or loans is another (better) option.

Quantitative easing (QE), the process whereby central banks create money to buy government bonds on a very large scale, mostly from banks, was highly unorthodox when first introduced to overcome the Global Financial Crisis of 2009. QE prevented the banks from running out of cash and defaulting on their deposit liabilities, thus preventing the destruction of the payments system that banks provide. But the banks, when selling bonds to their central banks, mostly substituted deposits at the central bank for previously held Treasury Bills and bonds. Bond holdings went down while deposits held by banks with the central bank went up by similar amounts.

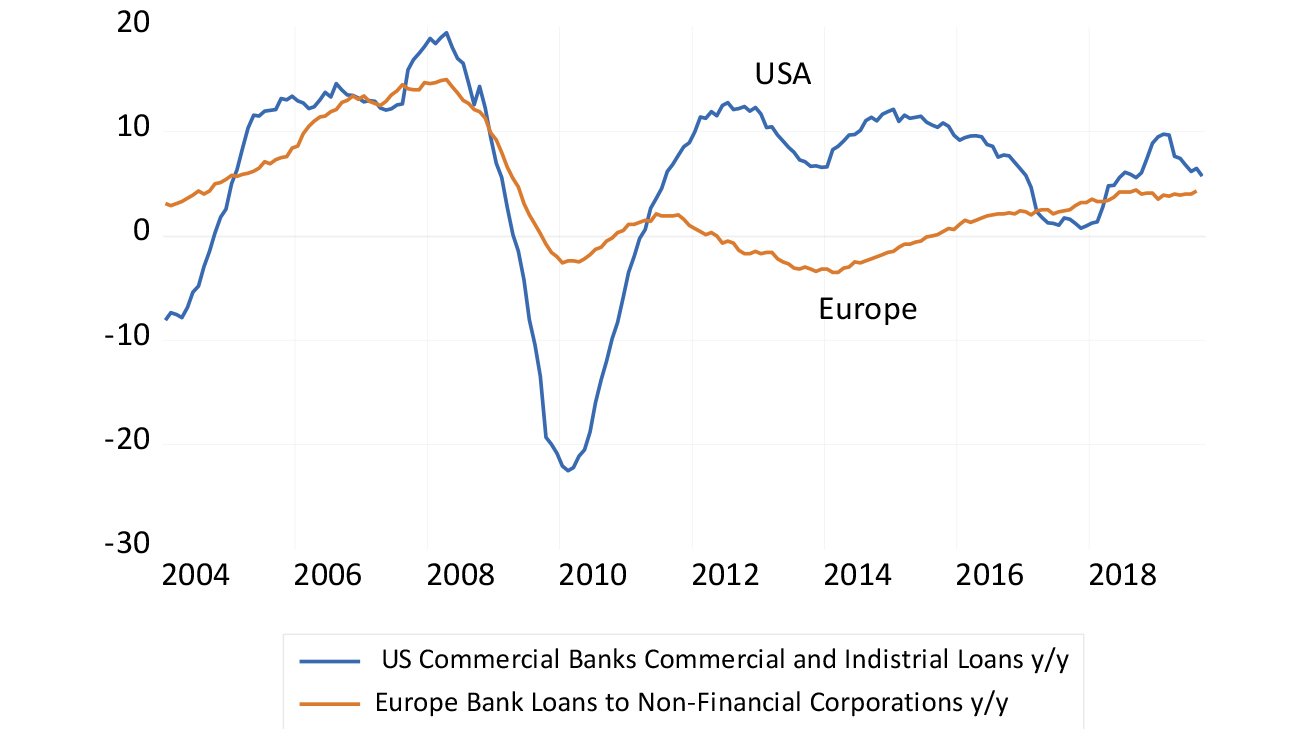

The banks did not (much) turn their extra cash into loans. It would have been more of a stimulus to spending had the central banks purchased assets from the customers of banks (retirement funds and their like) rather than the banks. Had they done more of this, the deposits of the banks, as well as the cash of the banks, would have increased immediately. The growth in bank credit and bank deposit liabilities has remained very modest, especially in Europe, though the recent pick-up in growth in bank loans is noteworthy. Hence the persistently slow growth in spending in Europe.

Growth in bank loans in the US and Europe

Source: Thomson-Reuters, Federal, Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment

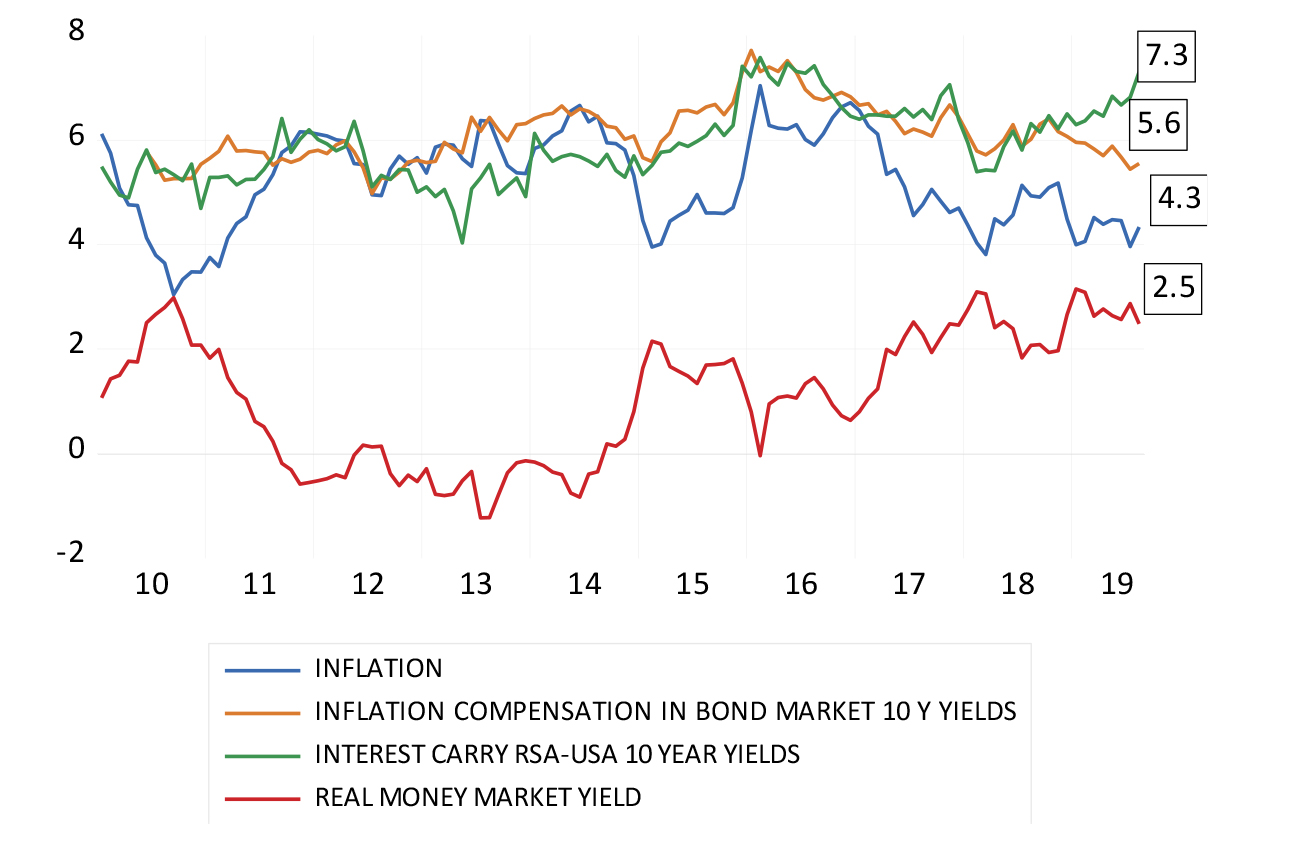

While the developed world struggles with low interest rates and subdued inflation (and expectations of inflation), the world of emerging markets presents very differently. Interest rates remain persistently high, with elevated expectations of inflation (and exchange rate weakness) to come. Accordingly, interest rates, after adjusting for realised inflation, remain at high levels as do inflation-protected interest rates.

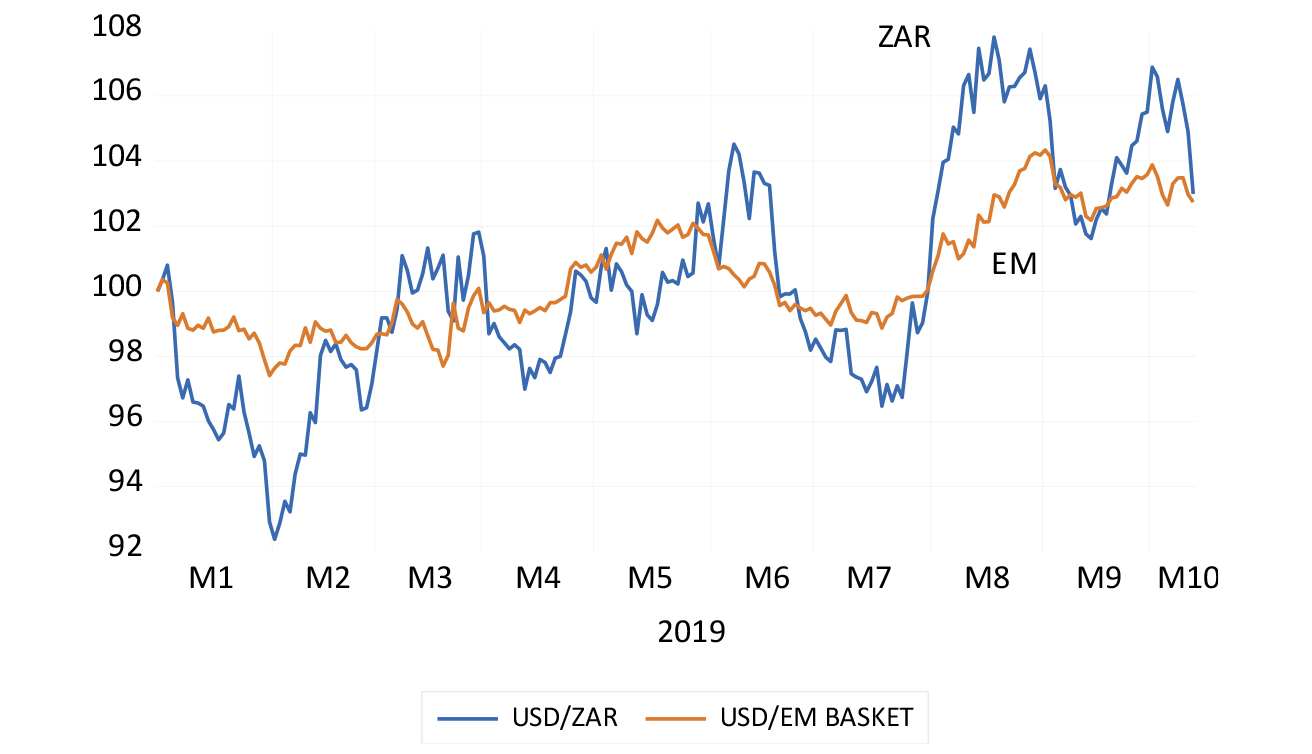

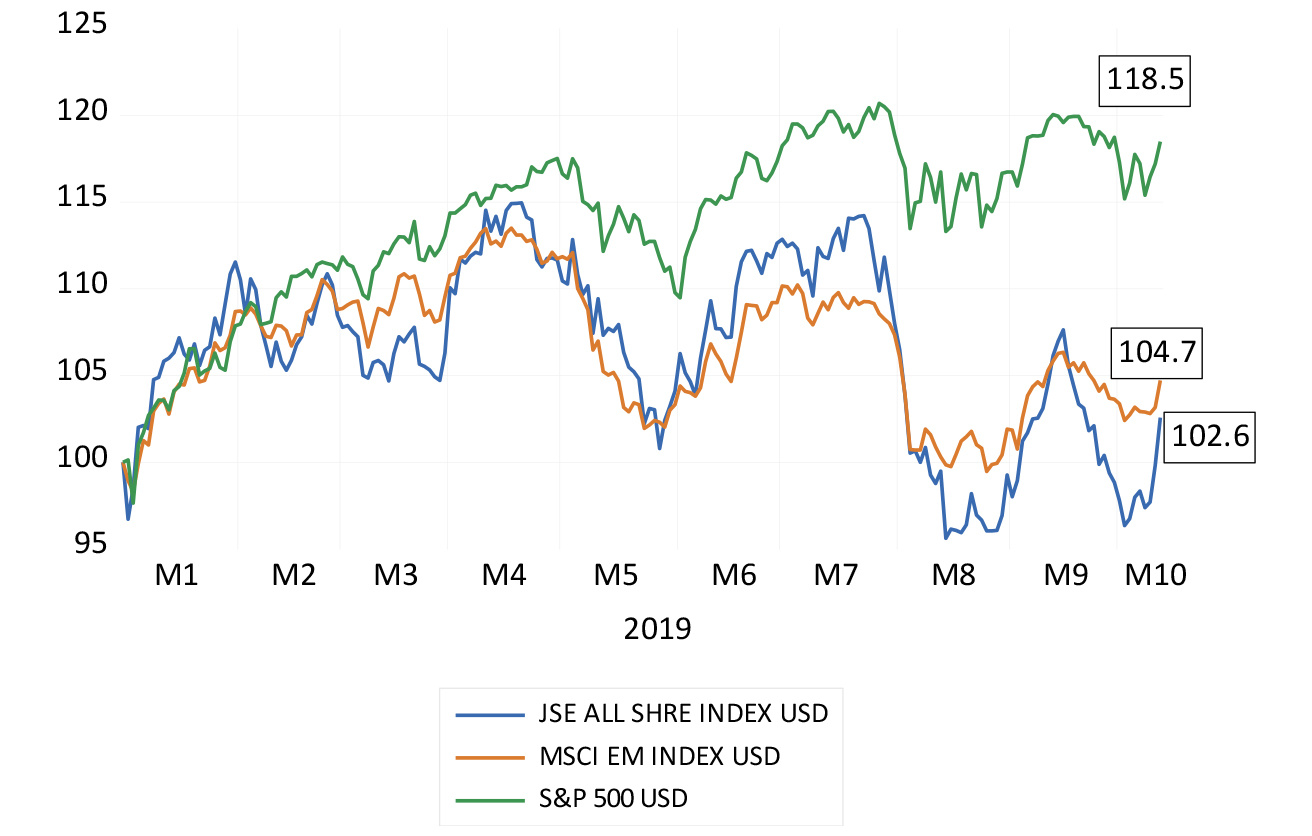

South African financial markets have continued to perform in line with other emerging financial markets. The JSE All Share Index gained about 2.6% in US dollar terms in 2019 (to 11 October) while the MSCI Emerging Market Index was up by 4.7 - both distinct underperformers when compared to the S&P 500, which was up by over 18% over the same period. The rand and emerging market currency basket had both lost about the same 2% against the US dollar over the same period (see figures below).

The USD/ZAR and the USD/emerging market currency exchange rates in 2019

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

The JSE and the emerging market equity benchmark in US dollars

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

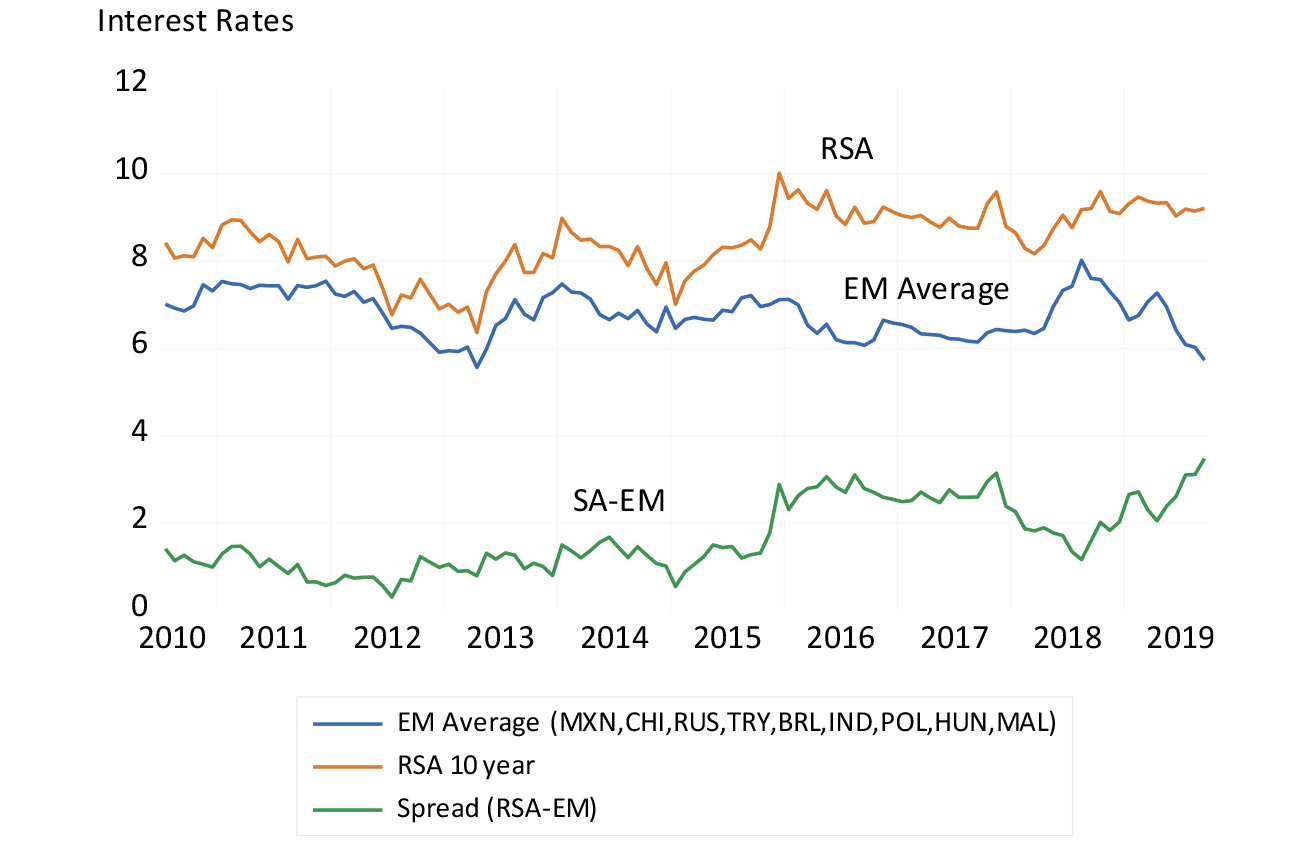

On the interest rate front, emerging market local currency bond yields remain elevated – above 6% per annum on average for 10-year bonds. While the average emerging market bond yield has edged lower in 2019, SA bond yields have moved higher this year (see figure below).

The market in SA bonds is factoring in more inflation and a still weaker USD/ZAR exchange rate. Unlike in the developed world, the cost of capital, that is the required rates of real return to justify expenditure on additional plant and equipment, remains elevated in SA. This means continued discouragement of expenditure, which is negative for the growth outlook.

SA and emerging market bond yields (10 year)

Source: Thomson-Reuters, Federal, Reserve Bank of St Louis and Investec Wealth & Investment

Capital remains expensive for SA borrowers and growth rates remain subdued.

Interest rates and spreads in the SA bond market

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

A combination of more inflation expected but with less inflation realised, because demand has been so subdued, has been toxic medicine for the SA economy. As in the developed world, the slack in the SA economy calls for stimulation in the form of lower interest rates. Unlike the developed world, there is ample scope for rate cuts.

The inflation expected of the SA economy reflects the well-understood dangers of a debt trap and that the SA economy will sometime in the future print money to escape its consequences. Yet fighting these expectations, which have nothing to do with monetary policy, with austere monetary policy makes no sense at all. Rather it means more economic slack, less growth, a larger fiscal deficit, and enhanced inflationary expectations. Eliminating slack with lower short-term interest rates would do the opposite.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox