What does a bottle of beer have in common with driving one mile in your car, or drinking one litre of milk, or binge-watching Netflix on a smartTV for five hours? They all have the same carbon footprint: roughly 1.2kg of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Poor old carbon dioxide. Of the 51 million tonnes of greenhouse gases emitted every year, CO2 accounts for almost 70%. It’s the most wanted criminal in the world today, and the most popular political football. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres put it recently in his summary of the latest IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report on global warming:

“Carbon dioxide and greenhousegas emissions from fossil-fuel burning and deforestation are choking our planet and putting billions of people at immediate risk.” (even though the full report doesn’t actually say that).

Perhaps he had looked at the following pictures. A tonne of CO2 occupies a volume of 535m3 at standard temperatures and pressures, equivalent to a cube 8m x 8m x 8m, or a balloon with a 10m diameter. If you were to fill balloons this large with the world’s approximately 90 million tonnes of daily emissions (let alone annual), the pile created would be big enough to almost cover Manhattan Island completely.

Figure 1: A tonne of CO2 in perspective

Source: Carbon Visuals, August 2021

As such, the world’s politicians and policymakers are determined to banish CO2 to the depths of hell, promising to completely eradicate its release by 2050 in a sweeping set of non-binding net zero pledges.

These are Herculean, almost impossible endpoints that will require an unthinkable level of global cooperation and a complete reset of the world economy centered around three critical requirements: significantly decarbonise power generation; completely electrify energy use and transportation; and dramatically improve the carbon efficiency of consumption.

Fortunately, some nearer-term milestones have been set. Over the next 10 years, to be on track for the 2050 commitments, the world will have to commission five times the amount of renewable energy capacity it has today. The number of electric vehicles sales will need to rise almost twenty-fold. And the carbon intensity of consumption will need to fall by 5% a year over that time. It’s this final requirement that is the topic of this piece today.

Thinking about your high-carbon lifestyle

Getting people to think harder about their high-carbon lifestyles is as crucial to the net zero transition as the need to clean up energy generation and use. It’s also going to be an extremely difficult undertaking, as decisions people make on food, housing, mobility, leisure and communication aren’t easy to shift, and politicians are unwilling to legislate for it. Instead, changes will have to come by osmosis, as people start to raise the importance of the carbon footprint of the products they consume, and more importantly as they begin to realise they are actually paying for it.

We call it Karbonskam, which is Swedish for “carbon shame”; a term that paraphrases Greta Thunberg’s flygskam (flight shame) used at her presentation to the United Nations in 2019. Like something out of Black Mirror, our carbon footprint will come to define many of us and our place in society, and it will come with a commensurate (and often indiscernible) cost.

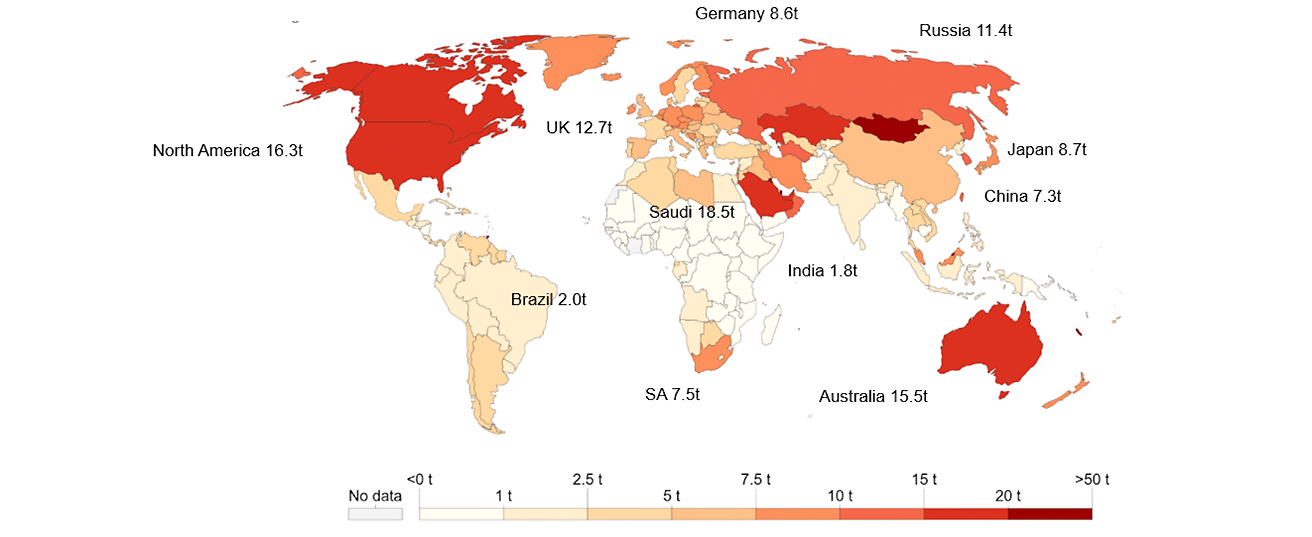

Carbon footprints around the world vary significantly. Fossil fuel-based economies, like North America (16.3t CO2 per person per year), Saudi Arabia (18.5t) and Australia (15.5t) have high carbon footprints, while most developing economies have lower scores.

Figure 2: Per capita carbon footprints around the world

Source: Our World in Data, August 2021

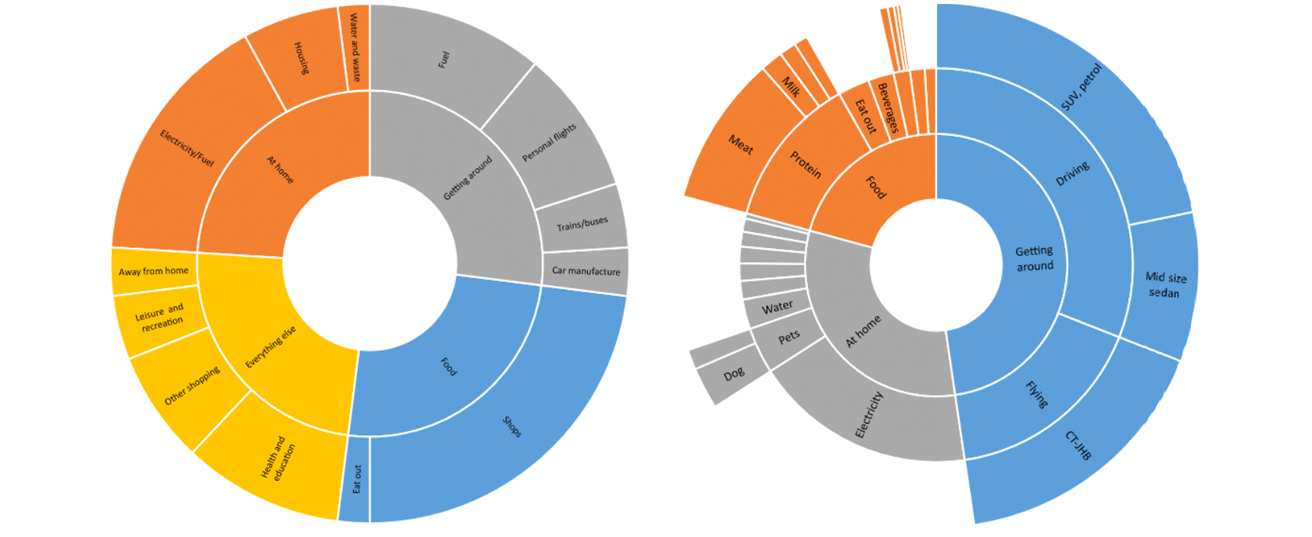

How do you calculate a carbon footprint? At a high level, it’s simpler than you think, since most carbon footprints are dominated by three main categories: getting around (i.e. travel), eating and staying at home. Within each of these, however, there can be significant differences in composition. For example, not everyone has pets (which have a sizeable carbon footprint), not everyone drives their car to work, while some people eat more meat than others, and others fly for business or pleasure more than most.

In the UK, the average person’s carbon footprint is about 12.7 tonnes of CO2 per year, and the contributions are shown in Figure 3 below. This figure includes a long-haul flight once every three years, one domestic flight a year, ownership of one car with standard efficiency driven an average distance per year, average at-home energy consumption and the assumption that meat is eaten most days. It also includes the embedded footprint of clothes and furniture purchased, as well as leisure and recreation.

In South Africa, our average carbon footprint is about 7.5t per person per year. At Investec, we have built a reasonably extensive database of carbon intensities (which will form the backbone of work we are doing for the business elsewhere) and we used this to measure the author’s own footprint, which worked out at 11.1t, split into the categories shown in Figure 3.

A large portion of this footprint is transport-related: two cars used to ferry three teenage kids around all day long; and four annual return flights to and from Johannesburg. A large portion of the at-home footprint is driven by coal-based power use (and three pets), while protein consumption is a significant proportion of the footprint left by food eaten.

Figure 3: Average carbon footprints in the UK and in SA (the author)

Source: Various, including: World Wide Fund for Nature, myemissions.green, South Africa TO, myclimate.org, World Bank, ourworld.unu.edu, VisualCapitalist,com, July and August 2021

As suggested above, your carbon footprint could end up costing you. In future, when you buy a car, the embedded emission will be disclosed and charged for. When you fill up, the fuel you purchase will carry a carbon premium that reflects the source of its production. When you fly, you will be charged for the carbon offsets the airline has to purchase on your behalf, or for the cost of the biofuels used. You’ll pay more for household lighting driven by coal-fired power than that by roof-top solar, and your use of incandescent 100W bulbs will be vastly more costly that 6W, energy-efficient LED lighting. The price of meat will reflect embedded emissions: beef may become almost unaffordable. And you may want to think twice before having another child or purchasing a second pet.

It all sounds very draconian, almost dystopian, but fortunately there are some relatively simple adjustments we can all make right now. Less travel, to begin with. Travel more slowly, share rides, use electric buses, and try not to fly anywhere or too much. Eat less meat and eat everything you buy (less waste). Don’t buy food with imported air miles and avoid packaging where possible. Upgrade your home: install a solar system if you have the means, install LED lighting, and consider installing a heat pump for the geyser. Avoid pets (sadly). And make a statement by changing your bank to one that has a serious environmental policy. Finally, tell your friends and family about what you are doing, without being annoying!

Karbonskam. Coming soon to a conversation near you.

Figure 4: Selected carbon intensities

772g

346g

1.5kg

15kg

300kg

63g

50 tonnes

1.056 tonnes

Source: Various, Investec Wealth & Investment research, July and August 2021

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox