On Wednesday 4 June 1913, Emily Davison picked up two flags in the Suffragette colours – purple, white and green – from the offices of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), of which she was a prominent member. She bought a return ticket from London’s Victoria Station to Tattenham Corner, Epsom, and boarded the train.

She had told nobody of her plans for the day, nor her motives. The events that would take place at the Epsom Derby that day would shock the nation and help to usher in the social change for which her movement had struggled for so long.

Emily Wilding Davison had been a literature student at Royal Holloway, and funded her own studies at the University of Oxford; however, the University didn’t give degrees to women at that time. Women were also denied the vote, and Davison soon began to dedicate her life to changing that fact.

As an activist of the WSPU, led by Emmeline Pankhurst, she undertook campaigning, civil disobedience and confrontational tactics to pursue universal suffrage in the UK. Her activism saw her sentenced to seven terms in prison, force-fed, and seriously injured after jumping down a staircase to protest the force-feeding of a fellow suffragette.

At the Derby in 1913, Davison waited at Tattenham Corner, the historic bend that forms part of the Epsom course’s unique challenge. As the first runners came past, Davison slipped quickly under the rail and ran out into the track. Her true intentions have been the subject of historians’ conjecture: perhaps she looked to cross the track, perhaps bring down a rider, or attach a Suffragette flag to a horse, or even target the King’s horse. As it transpired, the second group of runners included Anmer, owned by King George V and ridden by Herbert Jones.

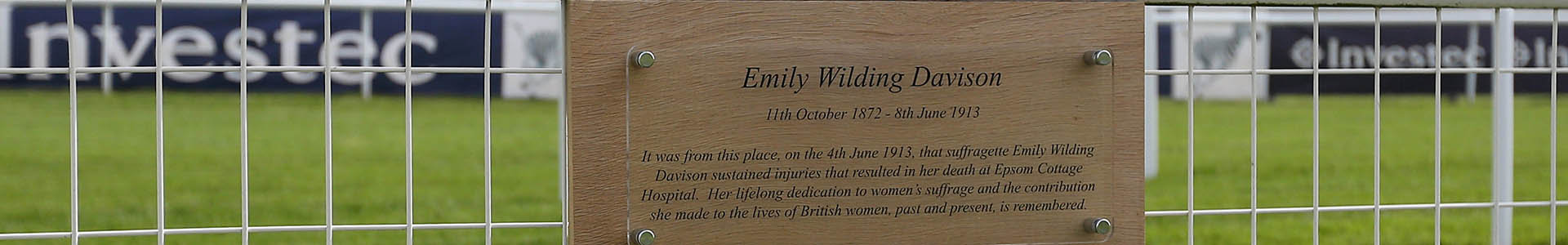

Davison was knocked to the ground by Anmer, who tumbled and threw Jones onto the track, who broke a rib and suffered cuts and bruises. Davison was taken to hospital with a fractured skull, but never regained consciousness and succumbed to her injuries four days later. The court’s inquest ruled that her death was due to ‘misadventure.’

In the aftermath of her death, Davison was criticised for her actions in the press, but the reaction from her movement was powerful. 6000 suffragists attended her funeral, and marched from Victoria Station to St George’s Church in Bloomsbury, dressed in white and holding white lilies. Her final resting place was Morpeth, Northumberland, and her gravestone’s epitaph read ‘Deeds not words’ – the slogan of the WSPU.

Davison’s death preceded the crucial role women played in assisting the British forces during World War One. In 1918, the British government finally gave some women the vote – those over 30 who owned property, or were married to a property owner. The 1928 Representation of the People Act finally extended the franchise to women over 21 – the same rights previously available only to men. Though Davison’s motives at Epsom in 1913 can never be known with certainty, their place in history is assured as a key milestone on the road to equality.

Search articles in