Inflation concerns rise as doves fly south for winter

Amid persistent energy and labour shortages and supply chain issues, inflationary pressures are starting to elicit responses from major central banks. In our latest Global Economic Overview, we see this materialising first in the UK, where we expect the Bank of England to announce a rate increase imminently.

The past month has witnessed the global economy still embroiled in energy shortages, logistical issues and labour scarcities. This indicates a worsening in the trade-off between growth and inflation, at least in the short term. Bond markets have expressed their concern. Breakeven sovereign yields and inflation swaps have moved to new highs as investors begin to doubt the transitory nature of these cost pressures. Major stock markets seem less affected – indeed, the S&P500 has reached new all-time highs. We have made only modest downward tweaks to our global outlook and are forecasting world gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 5.6% and 4.5% for this year and next. A danger is that central banks begin to act on the financial market signals, in which case growth prospects could look different.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) looks set to herald the start of quantitative easing (QE) tapering at its 3 November meeting, as members judge that substantial progress has been made on its inflation and employment objectives. We have trimmed our GDP forecasts to 5.8% and 3.8% for 2021 and 2022, down 0.2 percentage points in each case, largely reflecting supply shortages. Rebounding labour market participation should boost the size of the labour force in due course, easing supply shortages and capping wage pressures. We maintain our call that the FOMC will wait until the first quarter of 2023 to raise the Fed funds target, some six to nine months later than priced into short-term interest rate markets.

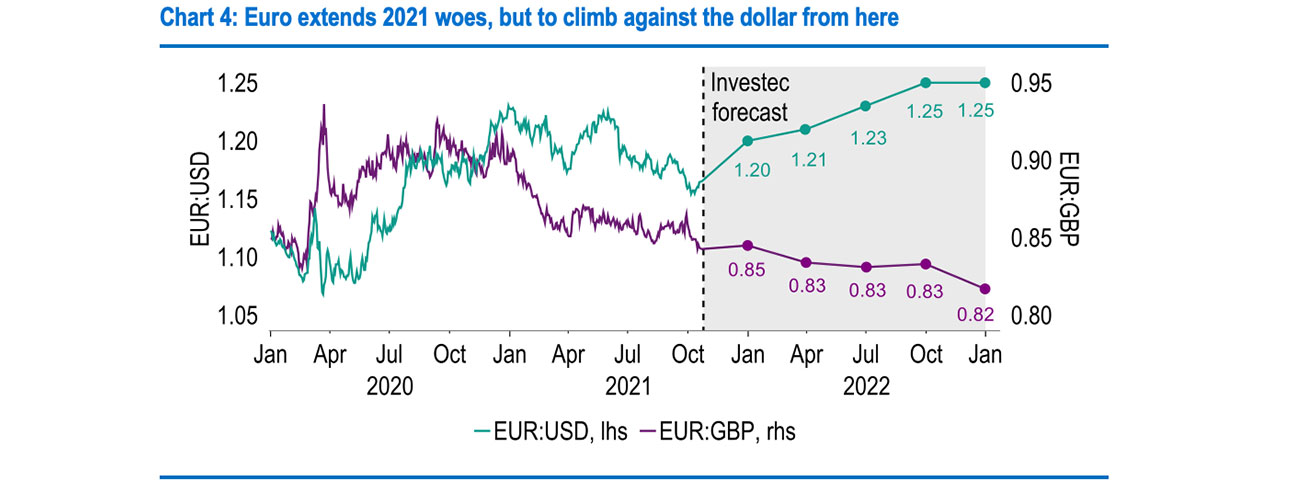

Given the latest weak production data, we have nudged down our euro-area GDP forecasts to 5.2% and 4.6% for 2021 and 2022, respectively – from our previous estimates of 5.4% and 4.7%. Meanwhile, Eurozone inflation expectations for the next five years are at their highest since 2014. Still, the European Central Bank (ECB) has maintained both its dovish stance and opinion that inflation will return below target in the medium term. We reaffirm our forecast for the ECB’s first rate hike in the fourth quarter of 2023. The euro has struggled recently, falling below $1.16 for the first time since July 2020. But we maintain our forecast for $1.20 by the end of 2021 and $1.25 by the end of 2022.

Substantial upward revisions to past GDP data have had the greatest impact on our forecasts this month, reflected in the 0.7 percentage points upgrade to our growth outlook for 2021 to 6.9%. Despite this higher base, our 2022 forecast has been pushed down slightly by 0.3 percentage points to 4.5%. Downside risks to this view remain, especially in light of surging Covid-19 cases and uncertainty regarding the labour market’s reaction to the expiry of the furlough scheme. However, we expect these risks will be outweighed by the current inflation concerns. Thus, it is likely that the Bank of England will hike the Bank rate by 15 basis points to 0.25% in its upcoming November monetary policy meeting.

Global

In its latest World Economic Outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made few changes to its GDP growth projections relative to July - it nudged down its 2021 forecast by 0.1 percentage points to 5.9% but kept its 2022 forecast unchanged at 4.9%. Over the same three months, we have cut our forecasts by 0.6 percentage points to 5.6% for 2021 and by 0.4 percentage points to 4.5% for 2022. The biggest downgrades were to the US, reflecting a disappointing labour supply. More broadly, energy prices have made a difference. Since the IMF put together its latest World Economic Outlook, oil price futures for December 2021 and December 2022 have moved up by 11.1% and 9.2%, respectively, and natural gas and coal prices have also surged.

For all but the energy-exporting nations, higher fossil fuel prices dampen GDP growth by boosting costs and disincentivising production. For China, the impact of energy costs on GDP is even more direct. Over half of electricity is still generated from coal-fired plants. As power prices have, to date, been tightly regulated – some liberalisation for energy-intensive industrial users has just been announced – power companies have not been able to pass on much of the cost pressures they are experiencing. Instead, the combination of high demand and less electricity generation, exacerbated by flooding in coal mining regions, has resulted in power outages. At least 17 regions have had to curtail industrial output to cut electricity demand.

The impact of reduced industrial output from China also has wider repercussions globally - it will add to the shortages of goods and further fuel the current pricing pressures faced by global supply chains.

Even though these shortages seem to have bitten particularly hard only from late September onwards, third-quarter Chinese GDP growth disappointed, expanding by just 0.2% quarter-on-quarter, which is well below recent trends. Therefore, we have cut our Chinese growth forecast since last month by 0.3 percentage points to 7.8% for 2021 and by 0.1 percentage points to 5.4% for 2022, respectively. The impact of reduced industrial output from China also has wider repercussions globally - it will add to the shortages of goods and further fuel the current pricing pressures faced by global supply chains. Still, this will prove transitory once the balance between demand and supply in China’s power market is restored.

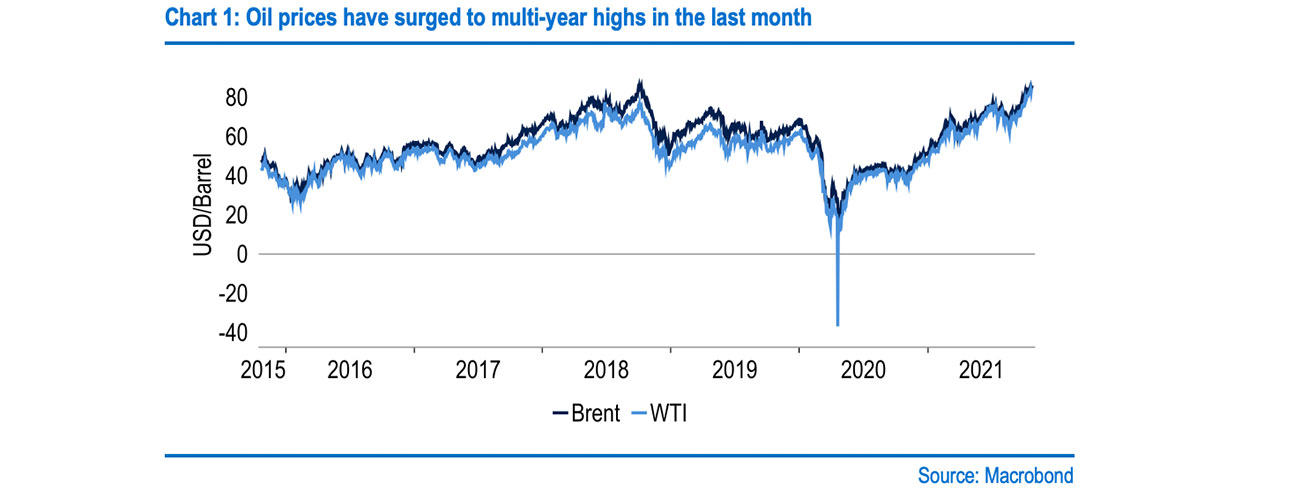

Energy prices have surged higher in recent weeks, with benchmark Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil reaching multi-year highs at $86 per barrel and $85 per barrel, respectively. This rise is leading to concerns over possible economic impacts. The White House has been in discussions with oil producers to help bring down costs, and there are suggestions that the US could release oil from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The surge in other commodity prices, such as natural gas and coal, is contributing to higher oil prices as the power sector and heavy industry switch to oil. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has suggested this could lift oil demand by 500,000 barrels per day over the next six months.

These commodity price spikes add to concerns over the inflation outlook and contribute to a rise in bond yields – as evidenced by the inflation component of nominal yields, with 10-year breakeven Treasury yields up 32 basis points since August. Markets are also reassessing the outlook for monetary policy, most prominently in the UK. This is particularly evident at the short end of the curve, where two-year yields hit a two-year high at 0.73%, as markets have moved to price in 100 basis points of tightening by the end of 2022. Bearing in mind widening term rate differentials with the US, we have adjusted our dollar-yen view. At the end of 2022, we are now looking for ¥120, compared to our previous estimate of ¥104.

United States

Ahead of the 3 November FOMC meeting, the committee’s intention to announce tapering its $120 billion per month QE purchases has become the worst-kept monetary policy secret. It seems likely that the Federal Reserve will aim to have ceased bond purchases by the middle of next year, which would leave it free to begin to raise the Fed funds target in the second half of 2022. Our base case forecast, helped by an expectation of inflation dropping sharply next year, remains that the first increase in the Fed funds target will occur in the first quarter of 2023. However, money markets have been steadily pricing in more hikes over the past weeks and now expect the first move as soon as the third quarter of 2022, with the funds target range at 1.00%-1.25% by the end of 2023.

Our base case forecast, helped by an expectation of inflation dropping sharply next year, remains that the first increase in the Fed funds target will occur in the first quarter of 2023.

The risk of a US sovereign default was once again averted close to the 11th hour. Democratic and Republican lawmakers agreed on a bipartisan deal to kick the can down the road by a couple of months, extending the effective deadline to 3 December. However, arguments over the Budget bill have occurred among Democrats, with ‘progressives’ and ‘moderates’ debating the size of the package. Reports suggest a compromise may be in sight, with a hefty slimming down of the original $3 trillion proposal, perhaps even to $1.5 trillion. What is not clear is whether the Democrats will attempt to end the filibuster or even abolish the debt ceiling at the same time.

Mounting fears over inflation have resulted in US Treasury yields rising across the curve over the past month, with 10-year yields reaching 1.70%, within 10 basis points of the high in March. This entirely reflects the inflation expectations – or breakeven yield – component, which has risen by 27 basis points to 2.66%. By contrast, real yields are 15 basis points lower. At the same time, 30-year mortgage rates have risen by 25 basis points from the summer’s lows, and overall mortgage applications have dropped by 15% since August’s highs. A weakening in various housing-related indicators may well follow, slowing markets' enthusiasm to push yields up. Accordingly, our 10-year Treasury forecasts remain at 1.75% for the end of this year and 2.00% for the next.

Meanwhile, record vacancies and a falling unemployment rate point to a strengthening labour market. As such, a number of Federal Reserve officials have stated that progress towards the employment goal has been met. However, as highlighted by the last two weaker-than-expected payroll reports, there are glitches – a relatively modest 429,000 jobs were added in August and September combined. Furthermore, a sluggish recovery in the participation rate, particularly within child-rearing and retirement age groups, is a point of interest. A recovery in participation over the autumn would help to ease labour shortages and cap some of the upward pressure on wage rates.

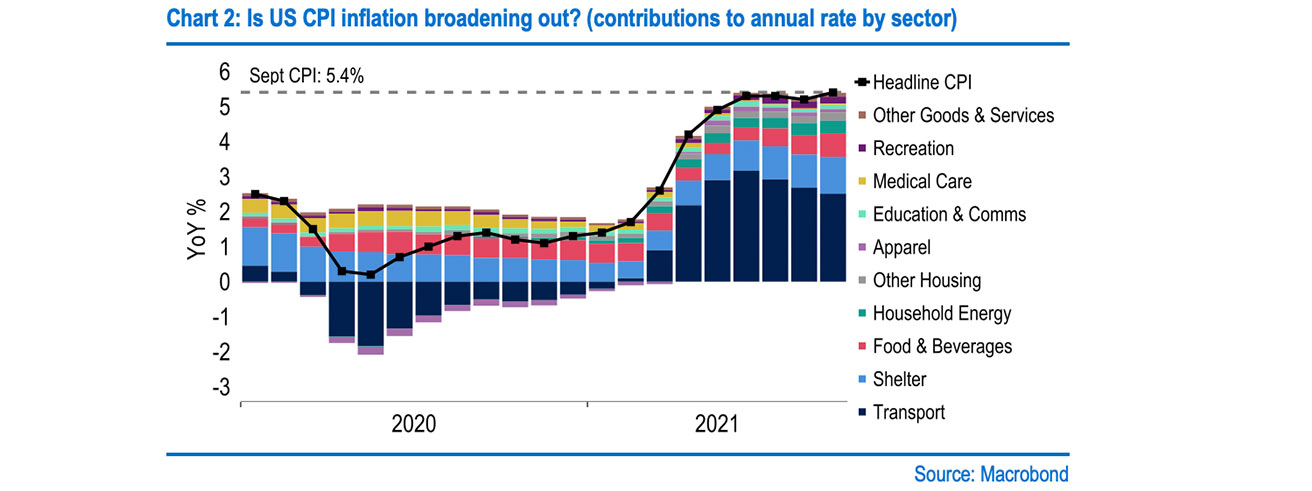

Surging inflation rates have led to a broad agreement that ‘substantial further progress’ has been made towards the Federal Reserve’s price stability goal – to avoid undershoots which have prevailed over the past few years. These price pressures are yet to cool, with headline inflation in September at 5.4% failing to ease back, despite some moderation in elevated areas such as second-hand cars. One danger is that price pressures are broadening. However, we do not expect high inflation to persist through 2022, especially without sustained wage pressures, which is not part of our base case scenario.

Although the US economic recovery remains robust, taking stock of the supply chain disruptions and the associated shortages, we have opted to downgrade our GDP forecast by 0.2 percentage points for this year and next, to 5.8% and 3.8%, respectively. A weakening in momentum due to supply constraints has been highlighted in the Fed’s Beige Book publications, in which mentions of ‘shortages’ and ‘slow’ have increased significantly. It is unlikely that this headwind to growth will ease in the near term – shipping group Maersk, which carries around 20% of all seaborne freight globally, has warned that disruptions will persist into next year. Aside from supply bottlenecks, rising mortgage rates also pose a downside risk.

Eurozone

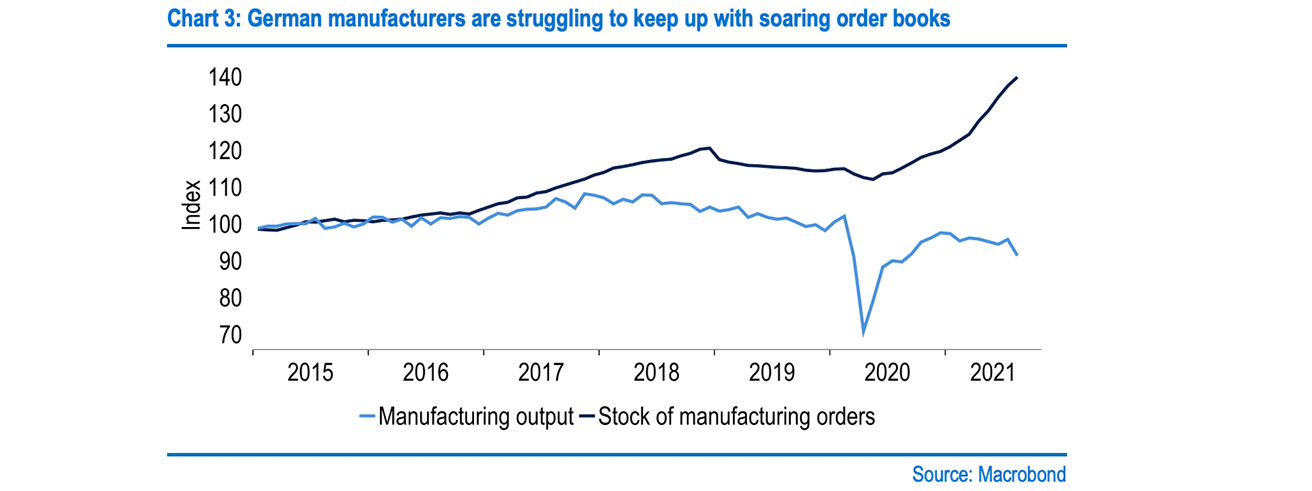

This month, we have nudged down our forecasts for Eurozone GDP by 0.2 percentage points to 5.2% for 2021 and by 0.1 percentage points to 4.6% for 2022. This is on the back of weak industrial production figures. In particular, Germany has been hit hard by supply chain disruptions hampering output. In August, manufacturing production was down 10.5% relative to pre-pandemic levels, whereas unfilled order volumes were up 21.7%. However, this has to be set against what looks like a very strong bounce in services. Accommodation and food service turnover volumes were up by a whopping 89% in August relative to the second quarter average. At the Eurozone level, our estimates are now that third-quarter GDP growth was on a par with the second quarter.

We have nudged down our forecasts for Eurozone GDP by 0.2 percentage points to 5.2% for 2021 and by 0.1 percentage points to 4.6% for 2022.

Certainly, output trends are not a major worry for the ECB right now. The bigger headache is the price picture. In September, inflation measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) climbed to 3.4% year-on-year. Although that leaves the third-quarter average outturn at 2.8%, only just above the ECB’s September forecast of 2.7%, its fourth-quarter forecast of 3.1% looks almost certain to be comfortably overshot - we are pencilling in a rate of 3.7%. Markets have taken notice, with the Euro Overnight Index Average (EONIA) curve now pricing in a chance of around 40% for a first hike by the ECB of 25 basis points by December 2022. This comes despite ECB policymakers stressing that current high inflation should prove transient and that the ECB’s forward guidance indicates more patience than is priced in.

An interesting turn is a personnel change. In a sudden move, Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann, an ECB Governing Council hawk, announced his resignation at the end of 2021. Whether the new German government – itself yet to be confirmed, but looking like a ‘traffic light coalition’ of SPD/FDP/Greens – puts in place a similarly hawkish replacement or opts for a more dovish president could have significant repercussions for the balance of discussions. Otherwise, the Governing Council looks stable. Of the directors and other ‘big five’ national central bank governors, only Banque de France head François Villeroy de Galhau’s term expires over the next year, and he has been nominated for a second term by French President Emmanuel Macron.

Of course, the key policy issue is the medium-term inflation outlook. September’s staff forecasts see HICP inflation at 1.7% in 2022 and 1.6% at the end of 2023. These forecasts seem certain to be lifted in December, but the broad assumption continues to be that the inflation spike is temporary, albeit exacerbated by energy prices. One factor the ECB will be watching is inflation expectations, where the five-year, five-year inflation swap has risen above the ECB’s 2% target for the first time in over seven years. Ultimately, the labour market remains the key determinant of whether the inflation backdrop feeds into serious wage pressures. At present, this has not occurred, but the ECB is monitoring developments in this space very closely.

Given inflation worries, bond markets have seen some notable moves of late, with 10-year bund yields reaching -0.08%, the highest since May 2019. Despite this, financial markets more broadly have not experienced a deterioration in risk sentiment. For example, there are no signs of tensions in euro area bond markets, with Spanish and Italian yield spreads stable over the month, while the primary market has remained strong, particularly in the green space. Admittedly, there has been some widening in corporate credit spreads, but in our view, the ECB probably still considers financial conditions to be stable. Aside from bonds, equity markets have been firm, with the Euro Stoxx 50 gaining 4% on the month.

We foresee the euro climbing to $1.20 by year-end, and a further gradual rally next year, to reach $1.25 in the second half of 2022.

The euro came under more pressure in the first couple of weeks in October, falling below $1.16 for the first time since July 2020. Since mid-October, it has regained the $1.16 level. We foresee the euro climbing to $1.20 by year-end, and a further gradual rally next year, to reach $1.25 in the second half of 2022. But sterling has outperformed the euro throughout this month. In fact, the euro-pound exchange rate has already fallen beneath our year-end target of 85p, after the Bank of England’s hawkish tone this month. We see this trend continuing, at least through 2022, with rate differentials likely to support the UK unit after some euro outperformance. We stand by our forecast for 82 pence by the end of 2022.

United Kingdom

Economic momentum has eased recently, as supply shortages have hit sectors such as the car industry. GDP rose by 0.4% in August, but only after a 0.1% retracement in July. However, for 2021 as a whole, the softer run of numbers is outweighed by upward revisions to prior data, for example, from the health sector. Overall, we now see UK GDP growth of 6.9% in 2021 and 4.5% in 2022, compared with previous estimates of 6.2% and 4.8%, respectively. Covid cases have risen again, averaging 50,000 per day. New cases are concentrated in younger age groups, especially secondary school children, where vaccination rates remain low. Indeed, the 10-19 age group accounts for 34% of cases over the past two weeks, despite this cohort making up just 12% of the population.

We now believe concerns over the path of inflation will prompt the BOE to raise rates on 4 November, with further 25-basis point hikes in both February and November 2022 to 0.50% and 0.75%, respectively.

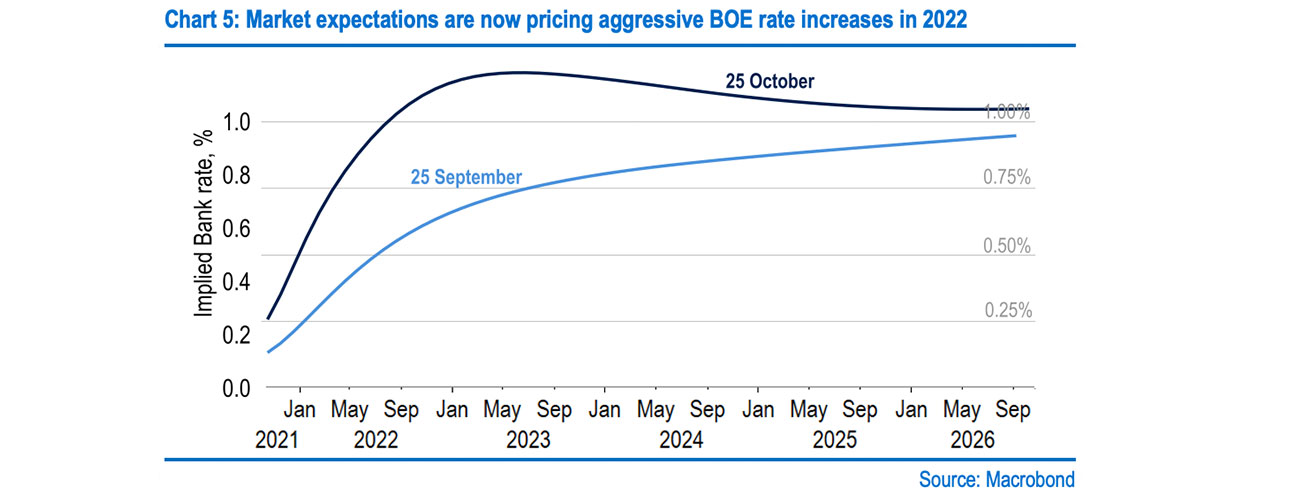

The government could invoke its ‘Plan B’, which involves compulsory mask-wearing and new working from home guidance, but another full lockdown looks unlikely. Interest rate expectations have rocketed over the past month, partly thanks to further signals from Bank of England (BOE) Governor Andrew Bailey that rates need to rise. Short-term Overnight Index Swap (OIS) rates are now fully pricing in a 15-basis point Bank rate rise to 0.25% next month. Indeed, we now believe concerns over the path of inflation will prompt the BOE to raise rates on 4 November, with further 25-basis point hikes in both February and November 2022 to 0.50% and 0.75%, respectively. Note that a 0.50% rate triggers an ‘organic’ reduction in the level of QE, with the non-replacement of £37bn of the BoE’s maturing gilts in 2022, reinforcing the monetary tightening.

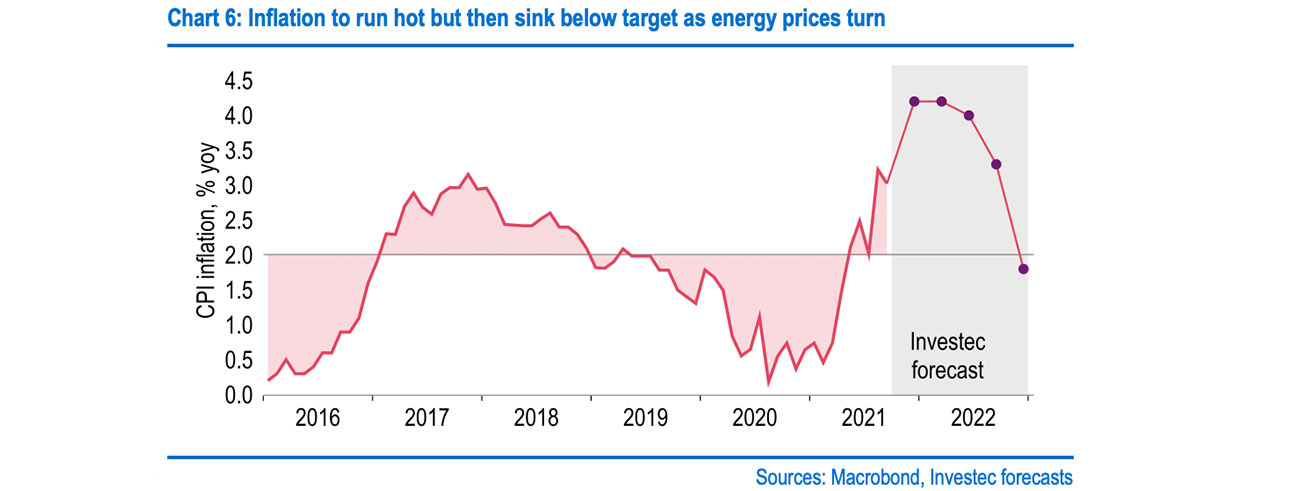

With supply chain issues and labour shortages biting, inflation nerves are evident within the Monetary Policy Committee. Chief Economist Huw Pill, for example, said inflation could rise above 5% in the near term. Our forecast looks for a peak of 4.3%. The Ofgem utility price cap rises in October to 12.2% and likely in April to 15% will provide upward pressure in the wake of the surge in wholesale energy prices. However, we see inflation dipping below target in the second half of 2022, as the energy crisis eases and negative base effects kick in. Nevertheless, the risk of more entrenched inflation is tangible if current labour market tensions persist and gains in pay growth drive a second round of price increases.

How far rates rise in part depends on how these labour market dynamics play out. Some one million jobs were on furlough when the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) expired in September, hinting that the jobless rate is set to rise from August's 4.5%. Moreover, labour force inactivity has risen by 345,000 since the start of the pandemic, and it is feasible that many of these people, for example, students, will return to the workforce soon, raising the amount of slack in the labour market. Ultimately, we do not expect a material wage response, underpinning our view that the Bank Rate need only rise gradually – to 0.75% by the end of 2022 and 1.25% by the end of 2023. It is also worth noting that the forward curve is more aggressive, but it is pricing in a risk of rates falling again in 2023.

Key risks to our forecasts stem from the outlook for wholesale energy prices. Gas prices have been increasing rapidly, rising by some 110% since August and resulting in the collapse of many energy suppliers. Although Ofgem’s energy price cap has been limiting the exposure of households to spiralling costs, the cap is set to be adjusted next April. How much it will rise by is uncertain – our projections assume a 15% increase. Hefty energy price hikes and higher inflation generally pose downside risks to our GDP forecasts via a hit to consumer spending. However, households currently hold an estimated £150 billion of excess savings, which may mitigate some of these risks.

UK households currently hold an estimated £150 billion of excess savings, which may mitigate some of the downside risks.

On 27 October, Chancellor Rishi Sunak delivered his third Budget. In broad terms, Mr Sunak continued to push capital expenditure as the primary way to achieve the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda. Fortunately for the chancellor, the recovery in the economy has far exceeded expectations at the time of the previous Budget in March, lifting tax revenues and reducing spending pressures, giving a much needed helping hand. Meanwhile, new fiscal rules are meant to help guide the public finances towards longer-term sustainability following the damage wreaked by the pandemic. Overall, the strategy may be to generate some headroom to reduce taxes ahead of a general election in December 2024 (or before).

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.