Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recently published a report on the physical science basis of climate change. The last such report was published in 2013, with updates released in 2018 and 2019, while the inaugural IPCC report dates back to 1990. The new climate report – released three months ahead of the COP-26 climate conference in Glasgow – tells us more of what we already know and suspect, and it will undoubtedly galvanise an acceleration of clean energy and decarbonisation efforts.

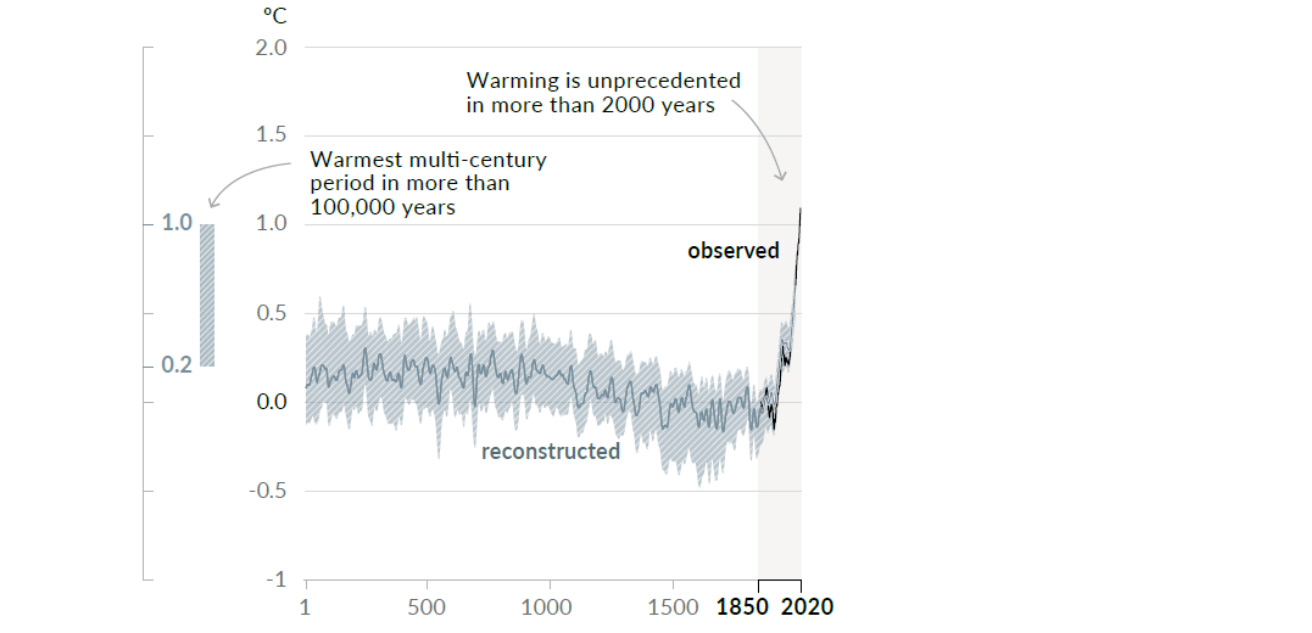

The key message in this report is that global temperatures have risen 1.1ᵒC from 1850-1900 averages (Figure 1) and will increase by 1.5ᵒC over the next 20 years. The report also confirms that human influence on the climate is now undisputed and that stabilising the climate will require “strong, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions”.

Listen to podcast

Campbell Parry joined Michael Avery on the business segment of Hot102.7 to share his thoughts on the implications of the IPCC’s new climate report.

Figure 1: Change in global surface temperatures

Source: UN IPCC Summary for Policymakers Report, August 2021.

We highlight a few of the key additional observations from the report:

- It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean, and land.

- Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations are at the highest levels in at least two million years (415 parts per million).

- Each of the last four decades has been successively warmer, with surface temperatures increasing faster since 1970 than in any prior 50-year period.

- Global temperatures have risen 1.07ᵒC from 1850-1900 averages, with larger increases over land (+1.59ᵒC) than over the oceans (+0.88ᵒC).

- Average global precipitation over land has increased significantly since 1950, with an accelerating effect from the 1980s.

- The global mean sea level has increased by 0.2m from 1901 – 2018.

As usual, the document uses scenarios and assesses the risks inherent in each. There are not many good outcomes, even in the most successful scenario. The concluding piece in the summary talks about our carbon budget. We have spent approximately 2,390 billion tonnes (gigatonnes, Gt) of CO2 since 1850 resulting in temperatures rising 1.07ᵒC. If we wish to maintain global warming at <1.5ᵒC with a 50% probability of success, then we can only emit another 500 billion tonnes of CO2. With our annual CO2 emission run-rate of ~35Gt (~51Gt if other greenhouse gases are included), then we have approximately 10-13 years left of our emitting behaviour.

As stressed above, none of this will come as a surprise to most, though the findings and conclusions of the report are perhaps a little gloomier than before. It must be remembered that it is a political document intended to scare the public and motivate politicians; Al Gore attested to this as recently as 2018. As such, it will likely serve as the basis for discussions in and around the upcoming COP-26 in Glasgow and will probably lift all decarbonisation efforts to a new level, especially on the part of developed world governments.

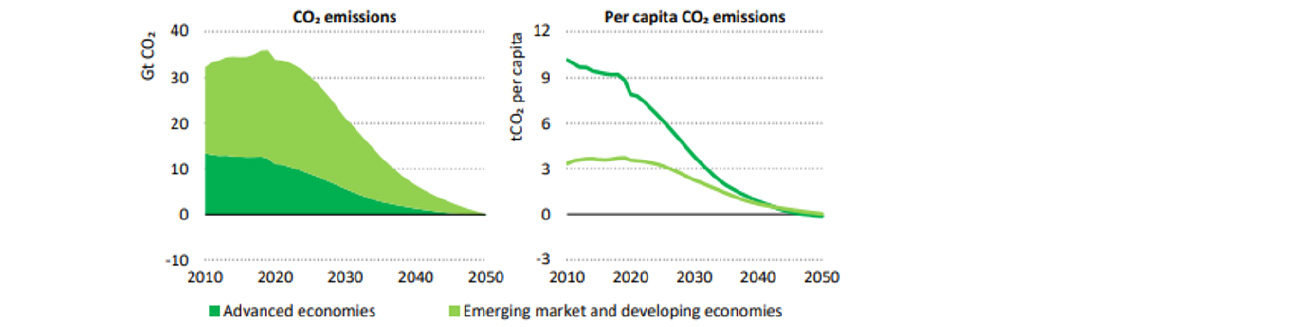

This is a good thing, but we may be too late. Net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 (Fig. 2) is the global goal laid out in the Paris Accord, but our analysis suggests that it is virtually untenable, and that it will require an almost unprecedented level of global cooperation and a dramatic reset in the world economy.

Figure 2: The shape of net zero by 2050

Source: IEA, August 2021.

Here’s why we think net zero will be a real challenge:

- Net zero pledges aren’t legally binding.

- Countries making up two thirds of the world’s GDP have made net-zero pledges, yet only the EU – which accounts for less than 9% of global CO2 emissions – has made real promises and outlined a tangible way forward. The rest appear to be paying lip service to net zero for now.

- The energy and consumption-efficiency effort that’s needed isn’t politically palatable. There is little chance of reaching net zero without a serious, fundamental change in political mindset.

- There is little chance of reaching net zero if US politics resets every four years. There needs to be full bipartisan buy in to net-zero targets in the US.

- There is little chance of attaining net zero without China’s buy in. China’s renewable energy goals are laudable, but its focus on coal needs to be completely reversed. China added 38GW of new coal generation capacity in 2020 and is set to add another 187GW over the next five years (Asia ex-China will add 130GW of coal generation capacity over the same period).

- We don’t have enough metals to meet China’s renewable energy goals, let alone the requirements of a global net-zero infrastructure.

- So far, renewables haven’t helped that much. Politicians have spent trillions of dollars on subsidising renewable energies with little effect on climate.

- China’s shrewd actions over the last five years to dominate the electron value chain (i.e. from the mining of metals used to electrify everything, to the manufacture of electric vehicles (EV) and renewable energy components, to the sale of EVs, and deployment of solar and wind generation) has national security ramifications for the west and will introduce complex new geopolitical equations.

Net zero will require 18 times the renewable energy capacity of 2020.

- Decarbonisation is far more fossil-fuel intensive than is widely understood, at least for the foreseeable future. For example, every US$1 trillion of green capex will raise oil demand by 100,000bpd, while an average-sized wind turbine contains 170t of coking coal.

- Net zero will require 18 times the renewable energy capacity of 2020. Given the materials intensity of renewable energy generation, this seems implausible.

- Hydrogen will be key to this transition, but the technology remains far from competitive or cost effective. “Blue” hydrogen – methane conversion to hydrogen with carbon capture and storage (CCS) – looks promising, but is still constrained by the lack of CCS options. “Pink” hydrogen – nuclear power used to produce hydrogen – makes imminent sense, but combines two very costly technologies.

- Carbon capture and storage is critical but, like hydrogen, it seems it will be a decade before this becomes a commercial reality. Net zero will require a 200-fold increase in carbon capture and storage.

- Gas gets an unnecessarily bad rap, and we believe it is key in at least making a start, especially insofar as switching over from older, coal-fired generation is concerned.

- Nuclear energy is best of all – it’s efficient, clean, provides good baseload power and the technology is well understood – yet there is little political incentive to build new plants.

- Biofuels can help but land use issues (i.e. how land used for biofuels competes with land used to feed a growing population) are a challenge.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, consumers will need to change their habits. It’s no good wanting the world’s governments and corporate sector to decarbonise if society at large is not prepared to give a little. Most importantly, consumers’ travel and meat consumption patterns must change. Without a global price on carbon, and premiums introduced for the carbon content of consumer goods, it’s unlikely such a shift will occur.

In summary, the IPCC’s new report sounds a louder alarm on global warming, and unless there is a concerted effort by all 195 member countries that are signatories to the Paris Accord, it’s unlikely we will achieve current emission targets.

Here are a few ideas that we think will help make a real difference, and faster: Embrace gas as an interim substitute for coal in older utilities. Start building nuclear power at scale, today. Introduce a punitive carbon price on everything – from transport fuels to aviation to meat to coal-fired power – and rotate the funds into planting trees and subsidising R&D in hydrogen production and carbon capture and storage. Support the mass deployment of renewable energies, but don’t forget the importance of mining in the supply chain; without mining, no clean energy will be possible. Finally, we think it's a good idea to force all companies to set annual emissions reduction pledges that are aligned with the 2050 Paris goals, rather than post vague long-term targets that incumbent management teams won’t be around to be held accountable for.

Responsible Investing and Sustainability at Investec Wealth & Investment

As Sustainability is core to our fundamental investment approach, we have integrated ESG considerations into our investment decision making and broader investment process.